Teachers are widely recognized as agents of change in society, playing a crucial role in shaping the minds, values, and behaviors of the next generation. Teacher as an agent of change means they have the power to influence students’ academic, social, and emotional development, as well as their perspectives on various societal issues.

Let’s delve into the details of how teachers can serve as agents of change:

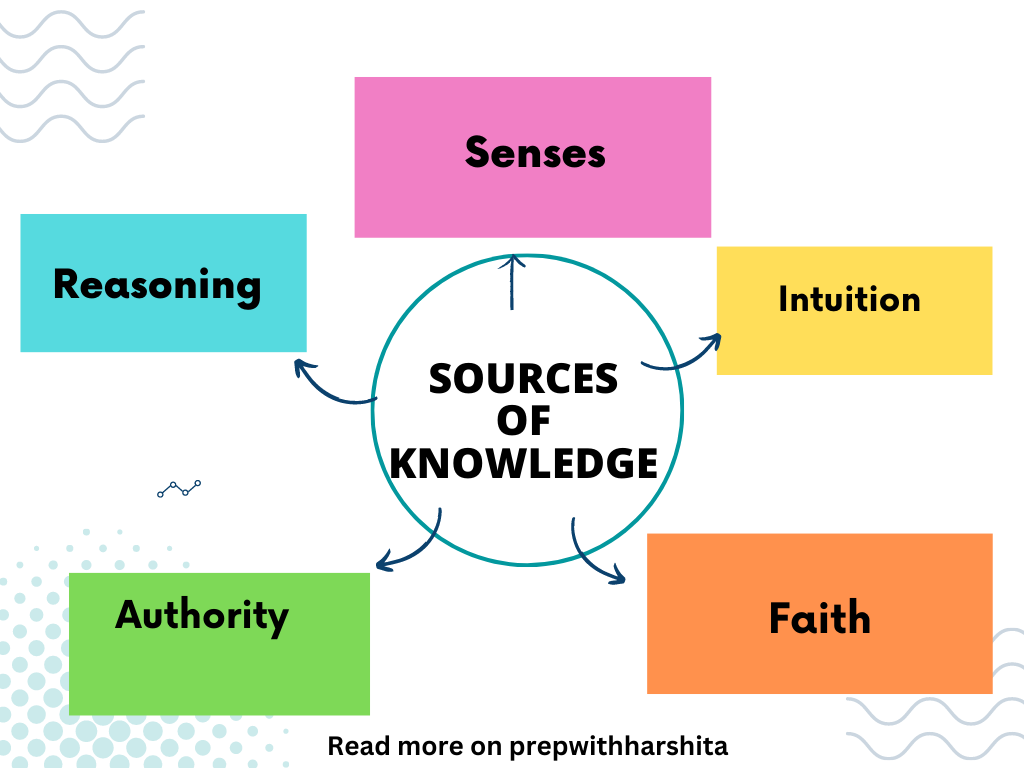

- Education and Knowledge Dissemination: Teachers are responsible for imparting knowledge and fostering intellectual growth among their students. By providing quality education and up-to-date information, teachers can empower students with the knowledge and skills needed to understand the world around them. This knowledge can challenge preconceived notions, debunk stereotypes, and promote critical thinking.

- Fostering Critical Thinking and Inquiry: Teachers have the opportunity to nurture critical thinking skills in students. By encouraging them to question, analyze, and evaluate information and ideas, teachers can foster independent thought and equip students with the ability to examine social issues from multiple perspectives. This enables students to challenge the status quo, think critically about societal norms, and engage in informed decision-making.

- Promoting Inclusion and Diversity: Teachers play a crucial role in promoting inclusion and embracing diversity within the classroom and school environment. They can create inclusive spaces that value and respect students from diverse backgrounds, cultures, and identities. By fostering a climate of acceptance, understanding, and appreciation for differences, teachers can combat discrimination and prejudice, creating a more equitable and harmonious society.

- Encouraging Civic Engagement and Social Responsibility: Teachers can inspire and motivate students to become active participants in their communities. By emphasizing the importance of civic engagement, social responsibility, and ethical behavior, teachers can instill values such as empathy, compassion, and respect for others. This can empower students to become agents of positive change, addressing social issues and contributing to the betterment of society.

- Modeling Positive Behavior and Values: Teachers serve as role models for their students. By demonstrating integrity, empathy, open-mindedness, and a commitment to social justice, teachers can influence students’ attitudes and behaviors. When teachers model positive values and ethical conduct, students are more likely to emulate these qualities and develop into responsible and compassionate individuals.

- Creating Safe and Supportive Learning Environments: Teachers have the responsibility to create safe and supportive learning environments where students feel comfortable expressing themselves and exploring new ideas. By fostering open dialogue, active listening, and mutual respect, teachers can facilitate meaningful discussions on social issues, encourage students to share their perspectives, and promote a culture of empathy and understanding.

- Collaboration and Partnerships: Teachers can collaborate with other stakeholders, including parents, administrators, and community organizations, to initiate and implement change. By forming partnerships, teachers can amplify their impact and create a network of support for addressing broader social issues, improving school policies, and advocating for educational reforms.

Teachers can play a significant role as agents of change in addressing gender issues within the educational setting.

Here are some ways in which teachers as an agent of change in relation to gender:

- Challenging Gender Stereotypes: Teachers can actively challenge and disrupt traditional gender stereotypes within the classroom. By promoting diverse role models, showcasing individuals who defy gender norms, and providing examples of people in non-traditional occupations or pursuits, teachers can broaden students’ perspectives and encourage them to question and challenge gender expectations.

- Inclusive Classroom Environment: Teachers can create an inclusive and supportive classroom environment that respects and values all genders. This involves fostering a safe space where students feel comfortable expressing themselves, regardless of their gender identity or expression. Teachers can establish inclusive classroom rules, ensure equal participation opportunities, and promote respectful discussions on gender-related topics.

- Curriculum and Materials: Teachers can critically evaluate and revise the curriculum and teaching materials to ensure they are free from gender biases and reflect diverse perspectives. This includes incorporating gender-inclusive language, incorporating literature and resources that portray diverse gender identities and experiences, and integrating gender-related topics across different subject areas.

- Gender-Inclusive Language and Practices: Teachers can model and encourage the use of gender-inclusive language and practices. This involves avoiding gendered assumptions, using gender-neutral terms when appropriate, and respecting students’ preferred names and pronouns. Teachers can also promote gender-inclusive policies, such as gender-neutral restrooms and dress codes, within the school environment.

- Addressing Gender-Based Bullying and Harassment: Teachers can actively address and prevent gender-based bullying and harassment within the classroom and school. This includes creating a zero-tolerance policy for such behaviors, providing education on respectful relationships and consent, and fostering a culture of empathy and support among students.

- Engaging Parents and Families: Teachers can engage parents and families in conversations about gender-related issues and collaborate with them to create a supportive and inclusive educational environment. By organizing workshops, parent-teacher meetings, or family events focused on gender equality and understanding, teachers can promote a collective effort towards positive change.

- Professional Development and Training: Teachers can seek professional development opportunities and training on gender-related topics. This can enhance their understanding of gender issues, equip them with strategies to address them effectively, and keep them updated on the latest research and best practices.

By actively addressing gender issues within their classrooms, teachers can contribute to creating a more inclusive and equitable society. They can empower students to challenge stereotypes, embrace diversity, and foster respect for all genders. Through their role as agents of change, teachers can help shape a generation that promotes gender equality and works towards dismantling gender-based discrimination and biases.

Also Read: Gender Stereotyping

Also Visit: Prep with Harshita